McLeod Group blog by Stéphanie Bacher, October 11, 2018.

We often hear about Canada urging other countries to respect human rights, most recently Saudi Arabia. But other countries also make recommendations to the Canadian government in order to help Canada improve its human rights situation at home and abroad.

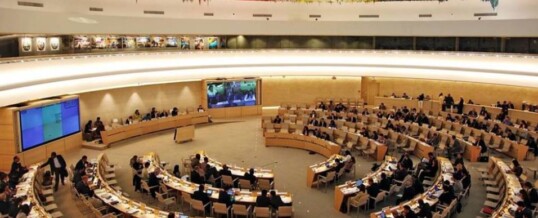

This year, it was Canada’s turn to undergo an assessment called the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) at the Human Rights Council in Geneva. At the review, other countries made a total of 275 recommendations to Canada.

Did the Canadian government use this opportunity to step up and make new, meaningful commitments? Although it took a few positive steps, Canada failed to commit to substantial advances and missed an opportunity to make a big difference by preferring to tout its current initiatives.

At the Human Rights Council’s session, Canada’s Ambassador to the United Nations Office at Geneva, Rosemary McCarney, announced that Canada had accepted 205 of the 275 recommendations and partially accepted another three. In particular, Canada agreed with recommendations to:

- Strengthen measures to guarantee the accountability of Canadian companies with regard to human rights abuses committed abroad and ensure access to remedies for victims;

- Fully implement the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and build mechanisms to operationalize free, prior, and informed consent;

- Ensure that all Indigenous reserves have potable water by March 2021;

- Implement all of the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in a timely manner; and

- Conduct investigations and ensure the collection and dissemination of data on violence against indigenous women.

Before delivering its official response at the Human Rights Council, the Canadian government initiated a vast consultation with civil society organizations (CSOs) and Indigenous groups to identify priority recommendations and practical suggestions for implementation. It co-hosted several events with Canadian CSOs, such as Canada Without Poverty, and invited civil society to submit written reviews by email or through its online platform. According to Alex Neve, Amnesty International Canada’s secretary general, CSOs and Indigenous groups were disappointed in the consultations because the suggestions made during those meetings were not reflected in Canada’s response to the UPR recommendations.

Moreover, Canada rejected several important recommendations, including the ratification of the International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169, providing the non-explanation that it is ʺnot currently under considerationʺ. Canada offered the same justification for its refusal to ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, even though the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Stéphane Dion, promised in 2016 that Canada would ratify it.

The Canadian government also refused recommendations to align its immigration detention regime to international human rights standards and obligations, notably concerning the length of time an immigration detainee can be held behind bars for non-criminal, administrative reasons – again, without providing a clear explanation. Canada likewise rejected the recommendation to establish a comprehensive national plan to address violence against women, stating that it was already putting in place numerous measures to address gender-based violence and that a national plan was not needed.

On foreign aid, Canada refused to commit to increasing the level of official development assistance (ODA) to reach the international target of 0.7% of ODA/GNI (gross national income). It justified its decision by stating that ‘’Canada has increased and is working to leverage its investments in international assistance’’, a surprising statement given the fact the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) recently criticized Canada for its lack of resources to match its ambitions and rhetoric (see our blog on the DAC report).

Ultimately, as Amnesty International Canada notes in its press release, ‘’the UPR of Canada is a missed opportunity to escalate human rights commitments’’ since Canada ‘’does not commit to substantial advances and primarily confirms initiatives already underway’’. As was apparent during the presentation of its national report in May (see our previous blog), the Canadian government seems to be more interested in rhetoric than using the opportunity to conduct honest introspection and pledge to improve its human rights record at home and abroad.

In 2017, Canada committed to developing a protocol and a stakeholder engagement strategy to coordinate implementation of international human rights obligations across federal, provincial and territorial jurisdictions, in consultation with civil society organizations. Since then, no concrete progress has been made. Canada should take this exercise seriously and, at a minimum, work with civil society partners in order to implement the UPR recommendations that it has accepted.