McLeod Group Blog, July 23, 2018

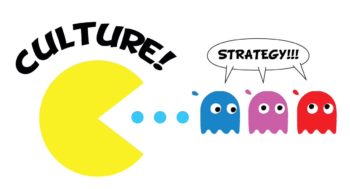

Corporate culture experts will tell you, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”. Making Global Affairs Canada fit for purpose to deliver on its Feminist International Assistance Policy (FIAP) is only partly addressed by ensuring that systems and work practices are up to date, and that staff have the necessary knowledge and skills. Any dissonance in culture among the international development, diplomacy and trade staff also needs to be articulated and addressed.

Culture tells you what is valued and rewarded in an organization. Is it gathering information and preparing policy briefs that enhance Canada’s place in the world? Is it understanding how social and economic progress takes place and being able to speed it up through the judicious use of taxpayer development cooperation funds in the health or education sector? Is it increasing mutually beneficial trade with developing countries? The experience, knowledge, and incentives required for these complementary objectives are not the same, and communicating across the cultures can be tiring and counterproductive.

For example, the three cultures work at different speeds. Development cooperation requires simple but efficient processes to move funds through the system, and needs understanding of how social, economic and technological change happens in a particular context. Diplomatic work can be both intensely pressured during a crisis and without rigid deadlines at other periods. Diplomatic work requires accurate analysis, while development cooperation requires a tolerance for risk and failure. Trade calls for competitive, assertive, quasi-private sector marketing behaviour and puts the emphasis on negotiating skill and knowledge of trade law.

Diplomacy and development cooperation differ in their approach to avoiding mistakes and learning from them. They may also give different value to field experience in a particular region and to knowing how to get things done at headquarters. The frequent rotation of personnel, inherent in the diplomatic service, is an obstacle to building in-depth thematic and geographic knowledge essential for development cooperation.

Here are three recent examples of how this culture clash plays out at Global Affairs Canada:

- A former Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) manager retired as early possible because, she said to a colleague, “I was tired of endlessly briefing and explaining to my managers who knew little and cared less about international cooperation.” Those managers were skilled in diplomacy.

- Andrew Caddell, a retired foreign policy officer, complained in the Hill Times that “Ex-CIDA folks have the advantage when it comes to promotion because they typically have more experience than their trade or foreign policy counterparts in managing staff and large budgets.”

- GAC staffers experienced in development cooperation needed to convince their trade counterparts that the most effective means of building trade in key sectors (such as natural resource management, transport or health) was not the promotion of Canadian equipment but investment in building educational, professional and personal networks that enabled counterparts to source appropriate Canadian goods and services.

These examples raise concerns about the quality of engagement and oversight at GAC, and the weight and support given to development cooperation.

Creating awareness of clashing organizational cultures is the first step to dealing with the problems they can present. When staff and leaders can name the norms and practices that are contradictory or counterproductive, they can take measures to address them. Leaders modelling and rewarding cultural behaviour appropriate to the work at hand comes next.

When the government merged development, diplomacy and trade into one department in 2013, it presented them as equal and complementary elements of Canada’s engagement with the world. Since then, it has (allegedly) integrated the supporting bureaucracy, though each area has its own minister. The current foreign minister is very trade-and-finance focussed, the recently shuffled international trade minister was very low key, and the international development minister virtually invisible except when announcing humanitarian assistance or FIAP-related funding. There is little evidence of complementarity or integration.

Most governments that have development responsibilities situated within the foreign ministry have a development cooperation directorate integrated into the ministry at the executive level, but with staff able to develop their career through in-depth knowledge and expertise in their area of work. Ireland, Norway, and the Netherlands use this model.

By contrast, GAC has decided that staff and units should be responsible for both development cooperation and diplomacy. It is time to revisit whether this is the best model. The 2012 OECD/DAC peer review of Canada noted that the attrition rate of development cooperation staff was high, and urged Canada to remedy the problem. This attrition appears to have continued, at a time when the government is proclaiming leadership in foreign aid. Is there some cognitive dissonance here?

The issue of clashing cultures requires urgent attention. GAC needs development cooperation leadership at the senior levels. It also needs to retain – and reinforce – a critical mass of development cooperation personnel with the knowledge, connections and experience to achieve development effectiveness and support realization of the Sustainable Development Goals through Canada’s FIAP.

Without this, the lofty rhetoric of the Liberal government, and its predecessor, will be just that – words. A closer examination of GAC’s cultures, and of the European models that permit both specialization and integration, can help GAC integrate its cultures successfully.