McLeod Group guest blog by Roy Culpeper, June 19, 2018

I first met Gerry Helleiner as a young professor, when I was an undergraduate at the University of Toronto in the late 1960s. He was teaching a course on the role of international trade and investment in economic development – for good or ill. His teaching focused on the practical: on how and why developing economies actually worked (or didn’t work well), and what sorts of international and domestic policies facilitate or undermine development.

For many students like me, frustrated by courses in economic theory with little relation to the “real world”, never mind applicability to the developing world, this was a breath of fresh air. Not surprisingly, students flocked to his courses, inspired by his passion about the development challenge, and many went on to satisfying careers as practitioners, researchers or academics.

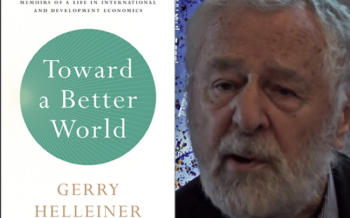

Now, 50 years later, Helleiner has published Toward a Better World: Memoirs of a Life in International and Development Economics. They will be fascinating to all who have been engaged in development practice, research and policy during the postwar decades. But they will also appeal to students and others contemplating careers in international affairs, and all those interested in deepening their understanding of how the developing world got to where it is today. Much of Helleiner’s account dwells on sub-Saharan Africa, the focus of his concerns and interests, where some of the most challenging problems persist to this day.

Helleiner’s career tracks the arc of development thinking, policy and practice over almost six decades. It is a testament to a man who has dedicated his life to helping create a better world, as the title of his memoirs suggests. But this is not a work of self-congratulation. Helleiner’s humility – not a strong suit among many professional economists – is evident and genuine throughout his narrative.

Early in his career Helleiner concluded that “external” development economists like him (from the North) could be of most help to developing countries in two ways. First, by helping reduce the international constraints imposed on developing countries by the rules of trade, the behaviour of foreign investors, and the policy conditionality of aid agencies and international institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF. Second, by building developing countries’ capacity to make policy decisions in their best interest.

Helleiner’s account illustrates how he fulfilled these aims. He was among the pioneers seeking alternatives to the much-criticized structural adjustment programs of the 1980s, particularly in Africa. He played an active role in seeking to reduce the debt burden on poor African countries. And he was active in bringing about a more balanced relationship between Tanzania and its donors. As for capacity building, he was involved in the genesis of crucially important institutions such as the African Economic Research Consortium and the African Capacity Building Foundation.

Helleiner is a consummate pragmatist who eschews dogmatism, whether of the Marxist or neoliberal variety. He describes his political orientation as that of a social democrat. As far as economic doctrines are concerned, he clearly leans toward Keynes, not the Chicago School. And while he is a stalwart advocate of the usefulness of empirical, evidence-based economic analysis as a contributor toward social progress, he fears that over the past few decades, economics has lost its way with its preoccupation with abstract modelling, econometric methodology and increasing recourse to the language of mathematics. He feels that those concerned with equity and social justice are unlikely to find in economics a discipline that is useful in addressing those concerns.

In Canada, Gerry Helleiner has enjoyed interacting with the development NGO community, as a speaker or resource person. He speaks with pride about being a founding board member, and later chair, of the North-South Institute, and laments its demise under the Harper government. His relationship with Canadian officialdom was often fraught. In one of his chapters, “Trying to Influence Canadian Foreign Policy”, he chronicles his many attempts over the years to make Canada less self-serving (or simply misguided) in its policies toward developing countries.

The memoirs conclude with a call for solidarity with the weak and vulnerable. He reminds us that considerable progress has been achieved by the world’s poor, but much remains to be done, and he appeals to his readers to keep up the struggle.

Roy Culpeper (Ph.D., University of Toronto, 1975) is proud that he was the first of many doctoral students to have Gerry Helleiner as his thesis supervisor.