McLeod Group blog by Lauchlan T. Munro, December 2, 2020

Results-based management is alive and well at Global Affairs Canada, but with a twist. Canada’s principal dispenser of official development assistance (a.k.a. “foreign aid”) has updated its International Assistance Results Reporting Guide for Partners in a way that incorporates changes to results-based management (RBM) that Nordic donors pioneered 15 years ago. Since Global Affairs Canada (GAC) has asked for feedback on its Reporting Guide, this blog offers an assessment. GAC’s latest guidance on RBM includes important and positive changes, but still lags behind where the project management literature and practice have gone in recent years.

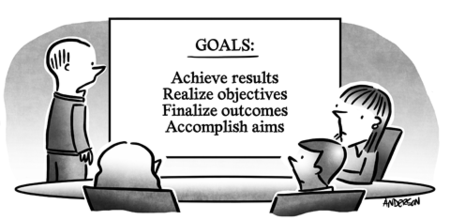

Results-based management is the prescribed form of public sector management, some would say ideology, in Canada and, indeed, throughout much of the world. As the name suggests, RBM insists that managers must first define the desired results that they seek to achieve, and then manage their activities and resources in such a way as to reach those results.

Officially, the Treasury Board defines RBM as “A comprehensive, lifecycle approach to management that integrates strategy, people, resources, processes and measurements to improve decision-making and drive change. The approach focuses on getting the right design early in a process, foussing [sic] on outcomes, implementing performance measurement, learning and changing, and reporting performance”.

In practice, RBM usually involves a lot of detailed upfront planning work for every project and in-depth periodic reporting on those results. RBM assumes that project managers can logically plan out all the steps needed to reach the desired results.

When RBM was still new back in the 1990s, what I call RBM 1.0, critics often derided it as being inflexible and excessively linear. In RBM 1.0, deviations from the original plan and its pre-set objectives were not tolerated. In 1997, a donor official roundly criticized me for using his government’s funds to help Rwandan refugees in the wrong Congolese province. My pleas that the refugees had left the province specified in the original project plan and had moved elsewhere fell on deaf ears.

Newer versions of RBM, which I call RBM 2.0, including the 2015 Treasury Board definition cited above and GAC’s new Results Reporting Guide for Partners, allow for “learning and changing” of operations in response to changing circumstances, even for changing project outcome objectives. In 25 recent interviews that I conducted with project managers at GAC, most respondents stressed the need for such flexibility in cases where the original plan becomes unfeasible for any reason. Changing or unforeseen circumstances and the evolving state of knowledge were the most often cited reasons for needing this flexibility. In this respect, GAC is like our Nordic partners, who recognized the rigidities of RBM 1.0 and embraced the kinder, gentler, more flexible RBM 2.0 over 15 years ago.

In its linearity, RBM 1.0 did not allow project managers to question the desired results of the project as originally defined in the project plan, even if they learned during implementation that the original objectives were invalid, unattainable or no longer relevant. RBM 1.0 drew inspiration from the way construction, defence and infrastructure projects were managed, and applied that linear logic to all other types of projects. Many scholars and practitioners have wondered if community development projects or institutional reform projects should be managed the same way as construction projects.

GAC’s Results Reporting Guide for Partners shows progress here too. It states that, “If there is a visible lack of progress on… outcomes, project implementing partners should review the theory of change and logic model to determine if flawed assumptions about how to achieve change require changes to these documents. With the agreement of Global Affairs Canada… changes to outcomes and outputs can be made” (page 19).

GAC’s Results Reporting Guide for Partners also embraces other progressive elements of RBM 2.0, such as the need to consider the project’s implications in terms of human rights, gender equality and environmental sustainability.

Still, GAC’s Results Reporting Guide for Partners contains elements of the old RBM 1.0, notably with its invocation of “best practices”, or prescribed optimal ways of doing things with more or less universal applicability. Management thinking and practice are now generally sceptical of best practices, favouring “best fit” approaches designed for different contexts and issues and agile management designed to cater to ever-evolving definitions of desired outcomes.

And while the Results Reporting Guide for Partners appears to allow for a fundamental rethink of project objectives in midstream, it is still a long way from requiring that projects be designed to capture and exploit the unintended consequences that are often so central to the projects. Medical research projects, for instance, are now often designed to capture these “off-target activities”. Indeed, in an era when even the venerable Project Management Institute devotes a tenth of its 700+ page Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge to “agile management” and circular, not linear, models of project management, GAC’s Results Reporting Guide for Partners looks decidedly old school.

Finally, the OECD notes that “results information can be used for accountability or as a management tool. These two purposes… have a natural tendency to conflict”. GAC’s Results Reporting Guide for Partners mentions both purposes, but the emphasis implicitly favours upward accountability and reporting over management purposes. This approach, combined with the “risk of excessive complexity” of Canada’s results system and GAC’s lack of RBM capacity at corporate and program levels, means that, in the words of the OECD, GAC’s “ability to experiment, to be responsive and innovate and to take responsible risks can be constrained by” both its own rules and Treasury Board’s “compliance and control mechanisms”.

In short, while the latest GAC documents include progressive elements of RBM 2.0, the old RBM 1.0 is alive and well in the Government of Canada. Getting to truly agile management of our aid dollars is still a long way off.

Lauchlan T. Munro teaches project management at the University of Ottawa’s School of International Development and Global Studies. Image: Mark Anderson.