McLeod Group guest blog by Joshua Ramisch, July 17, 2024

It was the scenes of violence – Kenya’s parliament burning, protesters shot dead on the streets – that captured world attention at the end of June. A week of peaceful protests against the 2024 Finance Bill and its significant tax increases had grown steadily larger and spread countrywide. When Parliament nevertheless approved the Bill, protesters’ frustrations and the subsequent police crackdown seemed to play into a familiar pattern. But this popular uprising is proving to be very different from its predecessors, in terms of both its incredible effectiveness and its structure.

Although global media has turned its eyes elsewhere, the Kenyan landscape continues to change at a frantic, unprecedented pace. “You leave the internet for a few hours and come back to find Kenya changed”, commented one Twitter/X user.

Initially, President William Ruto condemned Parliament’s invaders as “treasonous criminals”, but then a day later agreed to withdraw the Finance Bill. Subsequent state efforts to derail or coopt the movement through abductions or extrajudicial killings, or attempting “dialogue” with presumed leaders, have been rebuffed with more, peaceful demonstrations.

These culminated with a massive concert in Nairobi’s Uhuru Park on July 7 to honour the 39 people killed thus far by police. The concert’s charged atmosphere echoed rallies of previous generations: the 1990 protests (on that same date) that ultimately brought an end to single-party rule, and the ecstatic, pre-election celebrations of a united opposition about to finally gain power in 2003. Now, in this mass funeral-turned-concert, the name of each fallen protester read out was met with chants of “Ruto Must Go”. Four days later, President Ruto agreed to sack his entire cabinet. He looks increasingly isolated and weak. Demonstrations are set to continue.

The sources of frustration

The triggers for the anti-Finance Bill protests reflect what Nanjala Nyabola calls Kenya’s “polycrisis”: a cost-of-living crisis, amplified by COVID-era disruptions, confronting a public debt that now amounts to 68% of GDP.

This debt is the legacy of a decade of big-ticket infrastructure projects, many of which (like Nairobi’s elevated, restricted-access expressway) are literally out of reach for ordinary Kenyans. President Ruto came to power in 2022 ostensibly championing the working class “hustlers” against dynastic elites. However, his failure to deliver on promises like cheaper fertilizer quickly soured this relationship. Public outrage grew as his IMF-approved tax increases and austerity measures clashed with the perceived arrogance and incompetence of MPs and Cabinet secretaries who continued spending unchecked.

Gen Z’s turn?

Officials mocked demonstrators as misguided, middle-class youth, in love with their iPhones, Uber and fast food, calling them “out of touch with real problems”. By framing the protests as “youth-led”, both government and media play on Kenyan stereotypes of politically apathetic, social media-obsessed “Gen Z” (under 27), and of millennials (28-42) more interested in online activism than real organizing. Yet demographically, Kenya remains comparatively youthful. At the last census (2019), 66% of its population was under the age of 25 and 80% under the age of 40. Any mass movement in Kenya must necessarily reflect this youthful complexion.

“iPhone-loving” is also not much of a rebuke in a country where nearly as much of the population has a smartphone (58%) as has access to clean water (68%). My own research has shown how cellphones permit Gen Z and millennials to economically and socially support parents and younger siblings, if not extended kin and wider communities.

While a prominent government advisor, David Ndii, dismissed digital activism as “just wanking”, Kenyans increasingly use social media platforms to mobilize for change. After a surge in femicides in January 2024, users of the hashtag #TotalShutdownKE organized the largest-ever countrywide demonstrations against sexual and gender-based violence.

Canadian observers might consider TikTok the archetypal playground of Gen Z’s ephemeral challenges and fads, but Kenyans lead the world in the percentage of users (36%) who used TikTok to access news. This June, users uploaded videos explaining the Finance Bill and amplified their reach on Instagram and Twitter/X. “Live” spaces on Twitter/X hosted thousands during and after the Bill’s deliberation, and sometimes tens of thousands as protests and state reprisals continued. President Ruto even hosted his own livestream (with over 150,000 participants), after a televised interview did not quell the demonstrations.

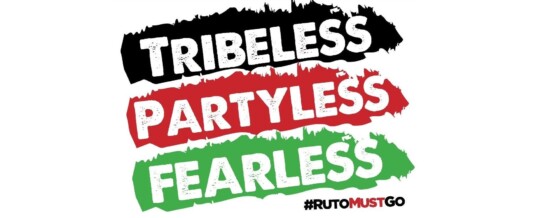

A final, distinctive feature of the current mobilization is its decentralized nature, defiantly reinforced in online messaging as leaderless, with slogans like “Tribeless, Partyless, Fearless”. Despite the involvement of social media influencers, prominent civil society activists and sports heroes, no singular or central leadership guides the movement’s actions. As Awino Okech noted, this inclusive, transparent and online process has kept the protests from being branded the puppets of any particular “foreign interest”, while also allowing Kenyans to unite across historically problematic divides like party affiliation, age, ethnicity and region. President Ruto’s efforts to engage “Gen Z leaders” in a National Multi-Sectoral Forum for dialogue or to join with opposition leaders in a government of national unity were instantly mocked and dismissed by protesters. The focus remains on longer-term institutional and ideological change.

What next?

The Finance Bill has been withdrawn, the Cabinet secretaries fired and even the much-hated police chief has resigned. However, no one has thus far been held accountable for the killings and abductions of protesters, or indeed the corruption and other misdeeds in government ministries. Plans are afoot to recall MPs and County Governors, while #RutoMustGo remains an overarching goal of Kenyans determine to reshape their country afresh.

Friends of Kenya, in Canada and elsewhere, should support measures to hold former government officials and police accountable for their actions. They could also join Kenyans in the diaspora to put new pressure on the IMF to rewrite the conditionalities placed on paying down the country’s massive loans. This chapter is far from over, but the relationship between Kenyans and their government feels forever changed. The success (or failure) of Kenya’s “Gen Z” protests will surely resonate far beyond the present moment.

Joshua Ramisch is the Director and a Full Professor at the University of Ottawa’s School of International Development and Global Studies. He has lived and worked in Kenya for over 30 years, and proudly marched alongside protesters in the early multiparty and post-dictatorship eras. Image: Widely circulating on social media, original source unknown.