McLeod Group blog by Stephen Brown and Gloria Novovic, October 18, 2022

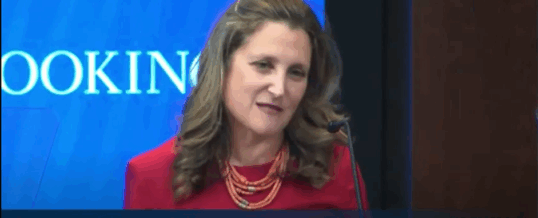

Canada’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland recently gave a headline-grabbing foreign policy speech in Washington, DC. At the event, hosted by the Brookings Institution on October 11, she outlined her prescription for the international order, which has since been described as the “Freeland Doctrine”.

Though refreshing for its plain talk, Freeland’s speech was oddly reminiscent of the Harper government in its overly simplistic Manichean view of good guys vs. bad guys. While she subsequently amended her statements on Canada’s lack of responsibility to support poorer countries, she provided no sign of the Liberal government’s claims of having a “feminist foreign policy”.

Manichean View of the World

Freeland unveiled her global vision, exhorting “liberal democracies” to rely economically more on each other (“friend-shoring”, which would boost Canadian exports) and less on autocracies as a response to what she called the return of “bloody politics”. Giving the Truman Doctrine a new spin, Freeland invited us to fight for a better world, one in which liberal democracies form international coalitions and isolate the “muscular dictatorships” and “petro-tyrants” of the world. The latter would be especially difficult, given the increase in Western dependence on the Gulf’s absolute monarchies as substitutes for Russia’s oil and gas.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as Freeland sees it, demonstrates the failure of international collaboration on the basis of economic interdependence and calls for more value-oriented approaches. In a simplistic analysis of the current global setting, Freeland’s speech was tinged with Cold War nostalgia and self-righteousness. Taking a page from Conservative Foreign Minister John Baird’s playbook, Freeland takes us back to a world of white- and black-hatted rivals, locked in a struggle for global power.

Not all Black or White

Freeland’s black-and-white portrait ignores the fact that most of the world’s countries are not actually liberal democracies or dictatorships. It also signals the continued prioritization of trans-Atlantic partnerships, constructed at the expense of global peace and security. Such government positions complicate the task of MP Rob Oliphant, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who is currently drafting Canada’s Africa strategy, further hampered by Canada’s COVID-19 vaccine hoarding and a discriminatory visa regime.

The Eurocentrism evoked an immediate negative reaction. An unnamed employee of the African Development Bank (ADB), of which Canada is a shareholder, diplomatically asked about the impact of the West reallocating funding for the replenishment of the ADB’s concessional loans fund to Ukraine. He pointed out that international financial assistance was required to help prevent democratic backsliding in Africa and counter Russian influence.

In her reply, Freeland minimized the impact of Western influence in Africa. She called on African citizens to assume responsibility and put their lives on the line to defend democracy, like she said was being done in Ukraine – omitting the fact that the West is providing the country with billions in assistance.

Freeland’s unscripted comments contradict the Liberal government’s prior commitment to peace, order and good governance abroad. More crucially, they raise doubts about the government’s understanding of the relevance of development assistance for Canada’s foreign policy. Canadian aid levels are far from meeting Canada’s global obligations, which makes the prospect of reallocating development assistance to military aid particularly alarming. Instead, Canada should urgently rethink how to contribute to fair solutions for global peace and prosperity.

Freeland has since clarified her position on international assistance. However, it remains imbued in a paternalistic promise she made in Washington, that “a helping hand is extended to all people everywhere who are choosing to do the hard work of building their own democracies”. Offering an updated and more informed perspective, Freeland stated yesterday that “we have a high level of responsibility” for problems in Africa and “We need today, if anything, to step up our engagement with the global south”. Toning down the paternalism, she added, “What is important is to take the lead from our African partners, and to listen to them about what it is specifically that is on their agenda, and what specifically they need”, which is the opposite of what she did at Brookings.

The Limits of Girlboss Feminism

In the absence of a foreign policy document and the long-awaited white paper on Canada’s feminist foreign policy, Freeland’s remarks offer a rare glimpse into the Liberal government’s perspective. Her position might signal “girlboss feminism”, focused on celebrating successful individual women. Otherwise, macho militarism is back, much like the Cold War mentality.

Freeland’s speech lacked any meaningful references to human rights or the societal transformation needed to uphold them. Her feminist allyship was restricted to praising women’s participation in the Brookings Institute event. Her enthusiasm for militarism is difficult to reconcile with feminist discourses of care, international solidarity, and complex, intersectional approaches to social and global justice.

Becoming less economically dependent on geopolitical rivals is a sensible policy. However, the Manichean “Freeland Doctrine” more generally is a throwback to the early Harper years, albeit updated with contemporary examples and concerns. Despite the Liberal government’s claims of having a feminist foreign policy, the substance of Freeland’s vision is hard to distinguish from the previous Conservative government’s perspective. With Liberals like these, who needs Conservatives?

Stephen Brown is Professor of Political Science at the University of Ottawa and currently an International Fellow at the Bayreuth Academy of Advanced African Studies, University of Bayreuth, Germany. Gloria Novovic is a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Ottawa’s School of International Development and Global Studies. Image: CPAC.