By Ian Smillie, December 30, 2019

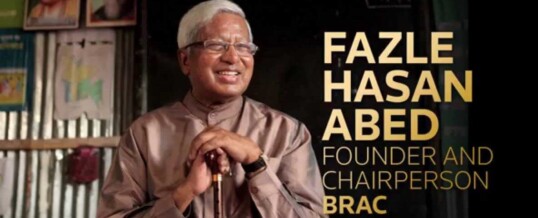

Several members of the McLeod Group had the privilege of knowing and working with Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, the founder of BRAC, one of the world’s top NGOs (see our recent blog). He passed away on December 20, and we wanted to share an appreciation of him with our readers. His biography can be found on the BRAC website. We offer our sincere condolences to his family, to BRAC, and to all those whose lives were touched by him.

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of BRAC in the global effort to end poverty. It is equally difficult to separate its success from the life and work of the man who created and steered it through almost five decades, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed – “Abed bhai” to his colleagues, “Abed” to his friends.

BRAC’s size and reach are – by any measure – staggering. Its microfinance lending, mostly to poor rural women, exceeds $1 billion a year. Although BRAC is a leader in the field of microfinance – touted for a few years as the miracle remedy for poverty – Abed never saw it as a cure-all. In his mind, the key to ending poverty was new, productive enterprise. Poor people, especially women and especially in rural areas, had to make things. And to do that, they had to be better linked to resources – seeds, fertilizer, knowledge, finance – and to markets. BRAC’s social enterprises in dairy, poultry, silk, handicrafts, seed multiplication, and a dozen other areas, have created hundreds of thousands of livelihoods, and in time they generated income that has made BRAC largely self-financing. Microfinance was the fuel in the tank, but the engine was always innovative, productive enterprise.

The BRAC Bank, completely separate from the microfinance operations, holds deposits of more than $2 billion and has a Moody’s long-term credit rating as good as that of Barclays Bank. Facts like these might catch the eye of a banker. But BRAC was and remains an NGO with its primary focus on social development, ranked for the past four years by the Geneva-based NGO Advisor as Number 1 on a list of 500 global non-profits.

BRAC pioneered non-formal primary education, mostly for girls, aiming to give literacy, dignity and hope to the next generation of mothers. Its groundbreaking oral rehydration training programs in the 1970s reached nine out of ten rural households in Bangladesh. That, along with innovative health, nutrition and sanitation programs, contributed to a seven-fold reduction in the country’s child mortality. Fewer child deaths, better education and more economic opportunity, especially for women, led to a three-fold drop in the fertility rate, ending worries about unchecked population growth.

There’s hardly an area of human development that BRAC hasn’t touched in a meaningful way, taking some of its best lessons to Africa and other parts of Asia. Fazle Hasan Abed did not accomplish this all on his own. But he was able to find and motivate others – individuals, government departments, donor agencies and some of the world’s most powerful and influential policy makers. His ambition was boundless, but it rested on a quiet charisma that inspired devotion and made mountains seem scalable. He listened far more than he spoke.

I first met Abed in 1973, when BRAC was just a handful of people working out of a flat in Motijheel. It was an unlikely, almost accidental enterprise, created by a man whose life until then couldn’t possibly have suggested what was to come. He had lived comfortably for several years in London, and then worked as a senior Shell Oil accountant in Chittagong. There, he took time off to spearhead relief efforts following the 1970 cyclone and the 1971 War of Independence.

Discovering the deeply entrenched poverty he had failed to notice during his privileged youth, he created what he thought would be a small, time-bound demonstration effort to show what might be accomplished with a few farming cooperatives, adult literacy and health training. A lesser man would have run from the resulting failures, but for Abed, they were lessons to be remembered and applied to the much bigger voyage on which he then embarked.

When I was completing research in 2009 for a book about BRAC, Freedom from Want, and trying to think about what had made it so successful, outsiders frequently told me it was Abed’s experience with the private sector. I always doubted that. Shell perhaps gave him useful perspectives on money and management, but it could not have been the source of his ingenuity, his compassion and sense of injustice, his willingness to take risks and his insistence on learning what works, what does not, and why. He told me that a lot of it was luck, and laughed, quoting Napoleon: “Give me lucky generals.”

I investigated the concept of luck and found a good summary: “Being ready for the opportunity.” Abed was always able, better than most, to see and understand opportunity. By that definition, “luck” may well have played a part.

He suggested I talk with an employee who had recently returned from doctoral studies in Britain – she might have a helpful perspective on BRAC’s success. She said she had expected to find a saint or a genius around every corner, but in the end, that wasn’t the case. The answer was “common sense” – everything BRAC has achieved came about, she said, through the application of common sense. I put that in the book, but in truth Abed did have the versatility of genius, a talent for applying common sense in a world where the concept is largely unknown and an ability to unlock doors long closed to innovation, justice and human development.

Abed never rested on well-deserved laurels; he always argued that “big” is essential in confronting poverty. Most ambitious people, however, leave a trail of wreckage and animosity behind them. With Abed, it was quite the opposite, and that too must be part of BRAC’s success – his unflappability in the face of tremendous odds and personal tragedy, his ability to build and to bring diverse people and resources together in common cause.

Sir Christopher Wren, visiting the construction site for St. Paul’s Cathedral, is said to have asked a stonemason what he was doing. “I’m cutting stone,” the man said. Further along, Wren asked another stonemason what he was doing. He replied, “I’m building a cathedral.” Abed was both Christopher Wren and the stonemason, and while BRAC in it many manifestations will continue to thrive, the legacy will always be his: Abed, Master Builder.

Ian Smillie is a development professional and foreign aid critic.