Blog by Stephen Brown and Hunter McGill, December 6, 2018

To help ensure that Canadian foreign aid is spent on supporting people in need in developing countries, rather than things like white elephants and Canadian commercial interests, Canada has legislation that mandates a focus on poverty reduction. The legislation also seeks to ensure that the government takes into account the perspectives of poor people and Canada’s human rights obligations when approving aid spending. The law is actually quite weak, but rather than strengthen it (as we proposed in a previous blog) the Trudeau government is stealthily trying to water it down even further.

Parliament adopted the Official Development Assistance Accountability Act, also known as the ODAAA or the Better Aid Bill, 10 years ago, under a Conservative minority government. The bill’s vague wording, adopted to ensure passage, minimized its impact. In fact, it is not clear that it has had any effect on aid, other than mandating some additional government reporting.

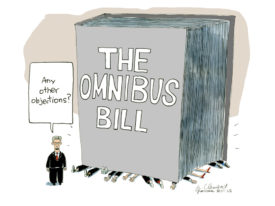

Given the Trudeau government’s desire to play a greater role on the world stage, not least through its ambitious Feminist International Assistance Policy, the time would appear ripe to reinforce the legislation so that it better meets its original goals. Instead, buried on pages 570 and 571 of the Liberals’ recently introduced 854-page omnibus “budget implementation” bill, are some provisions to weaken the act further.

In particular, the omnibus bill proposes to amend it in two ways: it would allow the government to redefine official development assistance (ODA) arbitrarily and dilute the government’s reporting requirements to the House of Commons on aid spending.

First, the bill seeks to repeal the legal definition of ODA, which currently follows international standards, negotiated carefully at the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD DAC), and instead define it via regulations. In other words, rather than being aligned with the international consensus of what can be counted as ODA, the new provisions will allow the government to include whatever it likes, and change the definition more easily and opaquely in the future. The committee studying the bill has proposed changing the bill so that cabinet “must take into account” the most recent OECD DAC definition of ODA.

Second, the bill proposes to amend reporting requirements to Parliament. It gives the government an extra six months to produce an annual report on aid spending, meaning that it could now be issued a full 12 months after the end of the fiscal year. The amendments also mean that the report would be “laid before” the House of Commons, instead of “submitted,” implying that it need not be debated and formally adopted.

Moreover, the government wants to eliminate the requirements for reporting back on Canada’s official positions at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (known collectively as the Bretton Woods institutions). Currently, under the ODAAA, and the Bretton Woods and Related Agreements Act, not only is the government obliged to report to Parliament on Canadian development assistance channelled to those institutions, but also on Canada’s votes and policy and priority initiatives taken as a member of the institutions’ governing boards. Since the World Bank is the largest global source of concessional development finance, Canada’s actions as a member of the board are important. If the amendments are passed, Canadians will not be able to track how the government engages with the World Bank, which receives about 10 per cent of Canada’s annual aid budget.

Every single one of these amendments to the ODA Accountability Act makes the Canadian government less accountable for how it spends the foreign aid budget. If it wants to regain credibility in the aid realm, the Trudeau government should instead seek to strengthen legal transparency and accountability measures.

In addition, amendments to the act should be adopted in a more transparent way, not hidden deep inside an omnibus budget implementation bill. The Liberals themselves condemned the previous Conservative government for presenting massive catch-all bills that are undebatable and therefore undemocratic.

This mechanism is all the more objectionable because the proposed changes to the ODAAA have nothing to do with the federal budget. It was for that reason that the Speaker of the House of Commons, Geoff Regan, split last year’s budget implementation bill into five parts, only one of which actually concerned the budget, and subjected each one to a separate vote.

In the current omnibus bill, immediately following the amendments to the ODA Accountability Act are provisions to enact a new law that will permit the government to “make loans to a foreign state or to any person or entity” and guarantee other actors’ loans. These measures are described as “international assistance.” An arbitrary redefinition of ODA, as described above, could allow, for instance, loans to Canadian mining companies operating in developing countries to be counted as foreign aid. How many other controversial measures are buried inside the omnibus bill and shielded from public debate?

This article was originally published in the Hill Times on November 28, 2018, under the title “Budget bill will reduce government accountability for Canadian foreign aid”. Image: Gary Clement, National Post.