McLeod Group Blog, January 26, 2018

When Global Affairs Canada (GAC) announced the Women’s Voice and Leadership program to support its new feminist aid policy, with a budget of $150 million over five years, observers hoped for the creation of a fund with a clear purpose, approach, and implementation that would support women’s organizations in developing countries. Canada already has experience with this type of fund, as it established regional gender equality funds in the period after the Beijing World Conference on Women in 1995 to advance the Beijing Platform for Action. However, the way GAC is currently developing the Women’s Voice and Leadership program may compromise its contribution to the very goals the Fund was intended to achieve.

Implementing the Feminist International Assistance Policy through the Women’s Voice and Leadership Fund requires more than simply providing funds to local women’s groups, as admirable as that goal is. It should also be an opportunity to explore new forms of North-South partnerships with civil society organizations and new roles for Southern women’s organizations.

It now seems clear that the “Fund” is not really a fund – with a coherent purpose, approach, and means of implementation. Instead, the allocations are notional, cobbled together from budgets managed by various parts of GAC – geographic and multilateral, and other areas such as peacebuilding. So it is mainly the geographic areas within the department that are developing projects, by identifying potential implementing partners, who will in turn fund local women’s groups. These units will also oversee the implementation, without a requirement for coherent reporting or learning across the projects.

There has been no transparency from GAC, despite continuing requests for more information about which countries and which partners are slated to receive funding. Informal information-sharing among potential partners indicates that of potential projects in at least 26 countries reportedly under consideration for the first allocation, only one local women’s organization is likely to receive direct funding. All other funding arrangements under consideration are grants to large Canadian or international NGOs or a handful of multilateral organizations, which will, in turn, support local women’s groups. Some of the large and capable Southern women’s funds were not invited to become implementing partners (such as the African Women’s Development Fund).

Failing to understand the implications of what is required to advance women’s rights risks squandering not only money, but also good will and results that vanish when the money is all spent. For example, Oxfam Canada provided funding for a small local women’s group in South Sudan that allowed them to meet with and convince local male chiefs to support ending violence against women. What made this effort powerful and effective was the opportunity provided through regional facilitation by Gender at Work for the women to work with other women’s groups in the Horn of Africa to refine their strategy, to share their learning and their achievements. It is not only the money, but the opportunity to analyze, strategize and learn with others that is more likely to make a lasting contribution to strengthening women’s rights.

The pressure is strong to fund local women’s groups. At least 50% of the money will go directly to women’s groups, according to GAC. However, money is power, and if the money is channelled through an intermediary organization, then women’s organizations are not building their relationships directly with the government of Canada. Moreover, in many cases, funds are being directed through organizations that are not embedded in local women’s movements. This also reduces the potential for investing in learning and scaling up at a national or regional level. This approach looks more like “business as usual” than like the feminist approach promised by the new International Assistance Policy.

To remedy this situation, GAC could consider the following options:

- Allocate a percentage of the program’s budget either to individual projects or on a sub-regional basis for learning and exchange among the groups that are funded.

- Bring together the GAC programmers developing the projects to increase coherence and learning potential among the projects by building a common framework for results and process, led by people with experience in developing and running gender equality funds. This group could decide to jointly manage monitoring and evaluation.

- Bring potential implementing partners and the Southern women’s organizations they plan to fund to a collective project development workshop with GAC programmers, rather than asking each GAC unit and each partner to negotiate their own.

- Insist that the grant application be a joint one between the international organization and local partners, to ensure transparency and mutual accountability.

- Before the current projects are finalized, and over the five years of the fund’s implementation, make a sustained effort to identify and support direct funding to Southern organizations to act as intermediaries and manage national and regional programs that provide funding and support to local Southern women’s organizations to carry out on-the-ground programs.

There is still time to step back and strengthen the process for and the results of allocating the Women’s Voice and Leadership funds. After all, isn’t that what a feminist international assistance policy should be about?

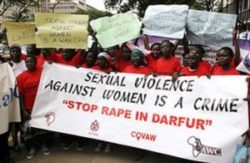

Photo: Kenyan women demonstrate against rape in Darfur, Sudan. Credit: UN Women.