McLeod Group Blog, Dec. 14, 2015

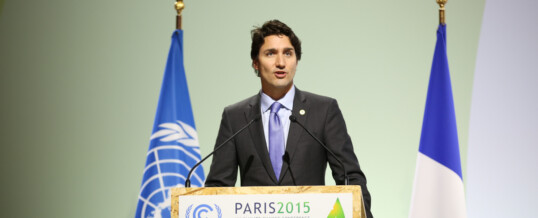

December 4, 2015 saw the first throne speech of the Liberal government. The speech carried the by now familiar ‘Canada is back’ message, one that has been very successful in drumming up international applause for the Trudeau government. The speech was very compact, essentially a set of headlines, recapping the Liberal manifesto and ministerial mandates, with an emphasis on current hot topics: refugees, re-engagement on climate change and Canada’s indigenous population.

It devoted just a single line to the challenge of global poverty.

Of course this speech was for a domestic audience, but tackling global poverty is critical for Canadians for more than reasons of morality or human solidarity. It is also about creating the stable world we need for our own economic future and security. A Canada that is ‘back’ needs to commit boldly to the global effort to end extreme poverty, the core goal of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (the renamed Post-2015 Agenda, which encompasses the Sustainable Development Goals).

The fact that the principle of universality (the idea that certain norms should apply to all countries alike) is enshrined in the 2030 Agenda makes it a domestic challenge as much as an international one. It will give extra impetus to domestic goals set out in the throne speech, such as the pledge to improve the well-being of Canada’s indigenous population. It should give a more inclusive meaning to ‘policy coherence’ than the narrow, self-interested version of the Harper government.

We know the path to reducing poverty both at home and abroad will be long and demanding. Canada will require a new approach to its relationships with the Global South, both the poorest, most vulnerable countries and the emerging economies with whom we seek enhanced economic and political partnerships.

The Development Minister’s mandate letter mentions an important starting point: broad public consultation on a future policy and funding framework for our international development agenda. This is welcome and implicitly recognizes that Canada’s aid program needs real change to fit today’s world. The consultation process should of course address the human and financial resources needed, but the ‘how’ is equally critical. A key dimension will be to ensure that Canada’s aid program, despite CIDA’s forced 2013 merger with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, remains developmentally driven.

A first, easy but symbolic step, might be restoring the name of CIDA as Canada’s public face as a development actor. It was deleted without debate in an omnibus budget—a mechanism now been banned by the Liberal government.

Another step would be a formal commitment in the first Liberal budget to increase aid. Maybe the 0.7% target is too big a first step, but we can at least act to help the poorest. There are two easily affordable options: First, Canada could meet the minimalist UN target of spending 0.15% of gross national income (GNI) in the poorest countries; or second, 50% of our aid could be devoted to the poorest countries. Canadians, when polled, have consistently supported increased aid. More aid for the poorest will provide concrete evidence that Canada really is back, reversing a trend for which we were widely criticized.

Over the medium term Canada must do much better. The UK’s Conservative government passed a law earlier this year to ensure that their aid budget remain at 0.7% of GNI. In contrast, Canada’s aid spending represented a dismal 0.24% of GNI last year. We need to put some money where our mouth is and we need to start now if we are to re-establish our reputation as a reliable, innovative and, most importantly, meaningful development partner.

International development and the effort to end poverty is a global agenda, one whose success—or failure—will critically shape Canada’s future. This is not about charity. The forthcoming Liberal budget will signal to Canada’s development partners whether or not we truly are ‘back.’